Course 1

WATERLINES

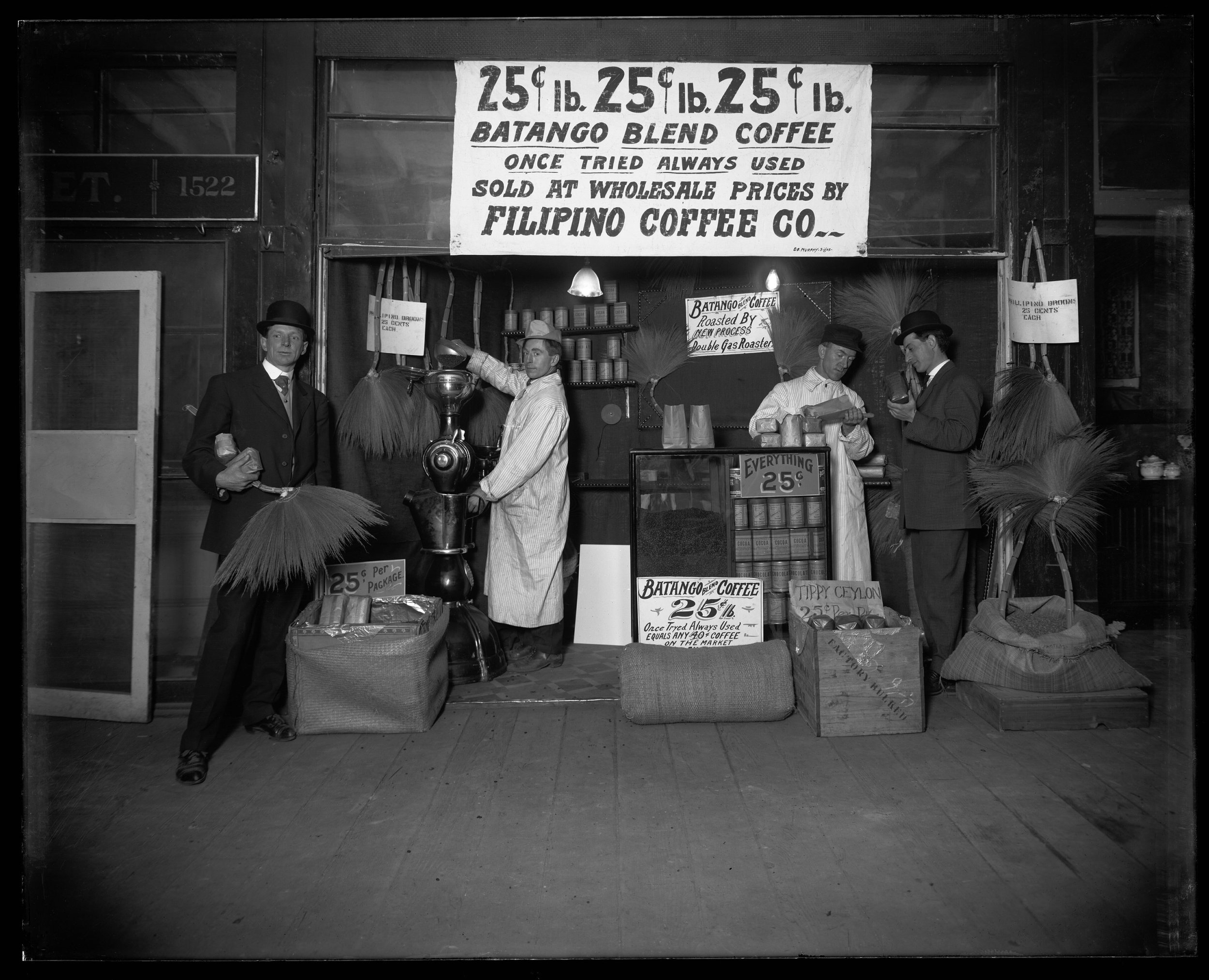

Archipelago, and all of Seattle itself is built on unceded lands of the Duwamish, Tulalip, and Muckleshoot Nations. For this, we must contend with our position as a fine-dining restaurant that is made possible directly through the stewardship of Native Nations, materially. Local cuisine in this way is a somewhat fraught idea, because it may inherently re- enforce the political boundaries of non-Native nations, thus contributing to erasure. Our presence on this land is through the non-White settler perspective, and we have tremendously powerful shared histories of solidarities, similar traumas associated with waves of colonialism, and form a global diaspora. As such, we do not subscribe to certain politically bounded definitions of what the Pacific Northwest is or is not. Instead, we look to the guidelines of "Bioregions", places that can be understood by their flora, fauna, and environmental characteristics. Not even to mention the acute ways that climate change has begun to shift growing seasons.

At Archipelago, our bare minimum is to be educated about our relations to land. Seattle also has an immensely powerful coalition of scholars, Native-led cultural and education hubs, and community initiatives where one can educate themselves on Native history and build relationships to Native communities. We also recognize that it takes work and vulnerability to build genuine relationships to our Native peers and this is a constant work in progress.

For us, we must contend with the fact that settler processes have directly affected Native sovereignty and have dramatically transformed the 'waterlines' of Seattle and the surrounding areas. The land that is now Seattle was once a vastly interconnected set of rivers and tributaries. Some of which, like the Black river, have entirely disappeared due to Seattle's settlement. Could you imagine yourself as a salmon, no longer able to make a journey back home on a river that had, until that moment, been there since time immemorial? Due to the engineering of the Montlake Cut, a major shipping route that connects the Puget Sound to Lake Washington, the flow of the entire water system reversed. Can you imagine the shock to your body, if one day, you had to adapt to breathing water and drinking air?

How can we truly be craftspeople who work with the life of the land and water without honoring its ability to remake itself? Salmon habitats, fields of wild Camas, control of traditional fishing places, are all bound up with our experience designed for you. This is the fundamental reality of food, and of a restaurant itself - that if designed intentionally perhaps can use its power as a node in a network to influence all of the areas that surround it. And we can do so with beauty.

Our Kamayan course - Kamayan meaning "eaten with the hands” is a bridge that combines Indigenous Filipino heritage with honoring the first peoples in Seattle. It is a playful introduction as well - inviting guests to use their hands to explore the flavors, textures, and presentation elements that make these first few bites so compelling.

This course sets the stage for what the experience. Without the scholarship of Coll Thrush, a professor of settler history at the University of British Columbia, and his work, The City of the Changers, we would not have the language and framing to understand how to address our presence as Filipino-American settlers working on defining regional FilAm cuisine by and for us. In particular, we can take this brilliant scholarship and help it come to live on beyond the page through cooking and craft.

The Waterlines mapping project created by the Burke Museum in collaboration with oral history is an example too of how research can live outside of the academy and a museum. Below are further resources that the team has used to understand our relationship to Native lands both here and elsewhere.