COURSE 1

PORTAL TO THE PACIFIC

There have been many ways Seattle has been thought of as a portal to the Pacific. Westward expansion, and colonial ideas and practices, positioned Seattle as a place that could easily spread America’s influence further west - to East and Southeast Asia. This colonial legacy has defined Seattle, and so too have the colonial processes that positioned individuals as subjects themselves. This is especially true of the University of Washington, which hosted the Seattle Yukon Pacific Exposition in 1909 to celebrate and promote the region’s ties to an expansive western frontier.

Further, infrastructural projects that have crafted highways though mountains, cleared forests, reversed and carved out river flows, and built-up and created land masses for the Port of Seattle to sit upon in anticipating the region’s global influence. People too, immigrants of all kinds and here, as we will see especially Filipinos and Fil-Ams, all left their marks on the city and the peoples that share Seattle's land and waters.

For Meryendas, which people of Philippine ancestry know as “snacks” or light meals, we are exploring the way that Seattle became a destination for many Filipinos both coming from the Philippines and arriving from other parts of the world. Seattle touches many a family story, wether we know it or not, and is a place of historic coming together that can both be rooted in history and with enough density to be imagined. In this course, the team thought of ways to connect Seattle’s longstanding history with the Philippine community to places of origin where Filipino and Fil-Am individuals passed through. For this course we draw inspiration from the locales and connectivities below.

LOUISIANA: One of the first permanent and documented Filipino towns in the US was St. Malo in Louisiana, dating to around 1830. At this time, both Louisiana and the Philippines were colonies of Spain. Drawn to the fishing industry, Filipino fishermen constructed large wooden buildings on Cyprus pillars seeming to float over the wetlands. Here, Filipinos found community with Black, Native, and Creole individuals creating a dynamic culture entirely their own. Crab boil in your adobo, anyone?

HAWAII: From Seattle and the Philippines many Filipinos, known as Sakadas, or “barefoot workers” made their way to Hawaii between 1906-1946. Contracted to work on the sugar cane fields, they were put into direct relationship with Plantation owners, Kanaka Maoli, and Japanese immigrants who worked alongside them. Over the years, they fought powerfully for their rights and shaped the region today.

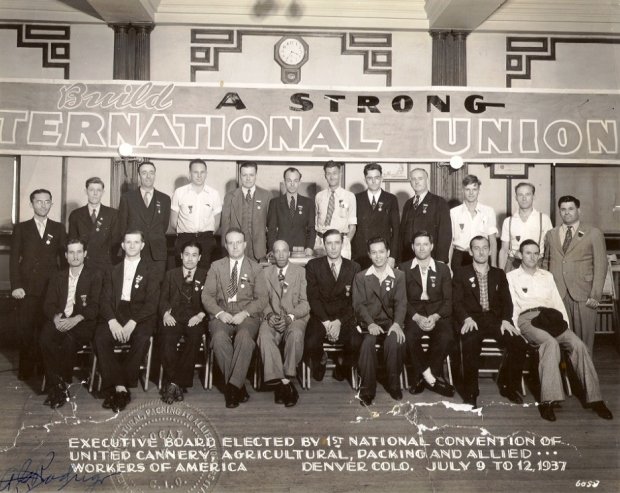

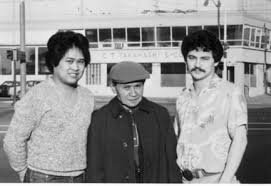

ALASKA: From the Philippines and Seattle, Filipinos defined and built the Alaskan Salmon Canning industry. Known as the Alaskeros, present in their ranks include individuals we talk about further in the menu - Victorio Velasco, and Maria Orosa. With their tenacity, they organized powerful Unions, wrote stinging newsletters full of drama and poetry, and faught to see historic desegregation in Alaska’s Stedman-Thomas disctrict.

CALIFORNIA: October 18th, 1587 marks the first landing of Filipinos at what is now known as Morro Bay in California. They departed from Macau on a Spanish Galleon Nuestra Senora de Buena Esparanza when the Spanish Galleon trade flourished between Spain’s colonies. Here, Filipinos landed on the historic lands of the Chumash peoples. (Fun fact, we did a whole dinner on this in 2022!)

At Meryendas, we frame this course as a collision of both the old and the new - layers and history of eating with one’s hand, cooking and transporting with leaves, and perhaps most importantly attempt to understand archipelagos of connectivity that go beyond what manifests often as a land acknowledgment - instead to try and tell stories of nuance and position highlighting assertions of sovereignty.

In this course we navigate the ways that Filipinos settled and moved across the US, forging solidarities and carving out histories of their own.

We encourage all guests to explore on their own and learn about Native history from Native scholars and community workers. Seattle has great examples, to start see: